Knott Laboratory provides forensic engineering and animation, Civil & Structural, and Fire & Explosion Investigation services to reconstruct accidents.

NASCAR Driver Tony Stewart and Kevin Ward, Jr. Fatal Racing Accident

The Stewart/Ward fatal racing accident occurred on August 9, 2014 at the Canandaigua Motorsports Park in Ontario County, New York.

Published July 24, 2018

By Dr. Richard Ziernicki, Ph.D., P.E., DFE, Steve D. Knapp, P.E, CFEI, CVFI and Angelos G. Leiloglou, M.Arch.

This fatal racing accident occurred on August 9, 2014 at the Canandaigua Motorsports Park (recently renamed Land of Legends Raceway) in Ontario County, New York.

Legendary NASCAR driver Mr. Stewart and Mr. Ward competed with their Sprint Cars and entered into Turn 1 at approximately the same time when Mr. Stewart attempted to overtake Mr. Ward. Mr. Ward lost control of his vehicle during the maneuver and made contact with the west edge track barrier where his vehicle came to a stop near the end of Turn 2.

After impacting the barrier, Mr. Ward exited his vehicle immediately. Because of this incident, the remaining Sprint Car racers went under a “yellow flag“. During a yellow flag, racers are alerted to exercise caution, and reduce speed for a hazard on the racetrack. Also, a caution announcement was broadcast over the drivers’ helmet headsets with instructions to stay low (towards the infield of the racetrack). As the Sprint Cars slowed for the “yellow flag” and caution, some of the sprint cars passed Mr. Ward’s stopped Sprint Car on the inside corner Turn2 of the track as Mr. Ward was walking behind the rear of his Sprint Car. As Mr. Ward began to walk towards the middle of the track, the right rear of the Stewart sprint car impacted Mr. Ward causing fatal injuries.

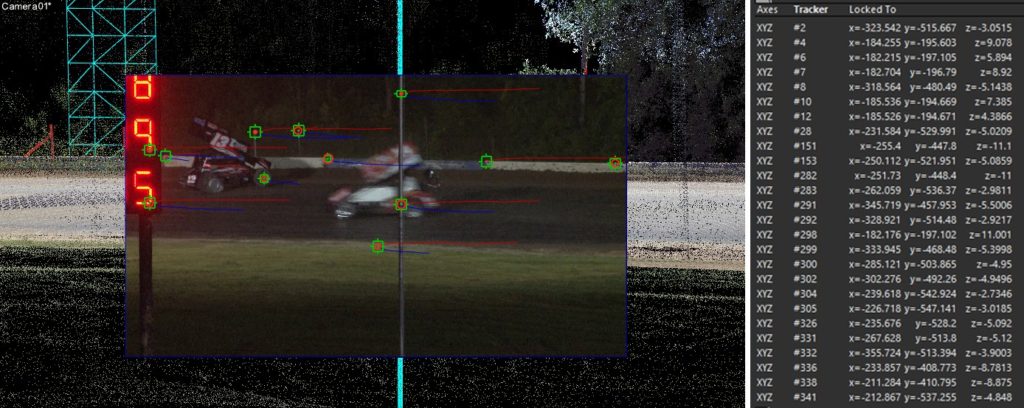

Videogrammetry Analysis of Track Video Footage

Knott Laboratory performed videogrammetry analysis on the provided race track video footage recorded by Mr. Bob Miller. The purpose of the analysis was to determine the spatial movement of Mr. Stewart’s vehicle, the preceding six sprint cars and Mr. Ward, the pedestrian, as seen on the video.

The videogrammetry analysis involved first using an established scientific process called “matchmoving”, also called “camera matching”, to define a virtual camera that “matches” the location, orientation, focal length and lens distortion of the camera used to record the provided race track video footage. Further, the matchmoving process determined where objects (seven vehicles and pedestrian) were located physically on the race track in each frame of the video.

Matchmoving

Knott Laboratory used dedicated software to perform the matchmoving process. First, two-dimensional points (features) were identified and tracked through multiple frames of the video. Each tracked feature represents a specific point on the surface of some fixed object on the race track (i.e. fence post, concrete barrier, scoreboard, etc.). Each tracked feature was then assigned and constrained to the feature’s corresponding three-dimensional coordinates (x, y, z) as defined by the race track point cloud which was captured using high-definition 3D laser scanning.

Using the tracked features and constrained points information, this dedicated software mathematically solved (“calibrated”) for a virtual camera (within the race track point cloud) that emulated the real-world camera that was used to record the race track footage. The virtual camera’s solution was determined to a high degree of certainty.

Once the camera was matched, each vehicle in the video was tracked and matched with a 3D virtual Sprint Car model in virtual space for each frame of the video.

Additionally, Knott Laboratory matched Mr. Ward’s motion by inserting a virtual bi-ped surrogate model into the virtual scene and tracking Mr. Ward’s body parts (legs, arms, head, etc.) in the video.

Summary

The analysis performed by Knott Laboratory using the provided video, high-definition 3D laser scan and matchmoving techniques made it possible to analyze sprint car movements, including speed and yaw angles at the rate of 30 samples per second.

The analysis showed that Mr. Stewart’s driving actions differed significantly from the six competitors who passed Mr. Ward prior to the incident.

Plaintiff claimed that Mr. Stewart intentionally spun his rear tires to put the sprint car into a yaw motion and to kick up dirt and pebbles onto his competitor Mr. Ward, a technique that is known as “stoning” in dirt track racing. Plaintiff further claimed that during this maneuver Mr. Stewart misjudged the sprint car path clipping and killing Mr. Ward. Mr. Stewart denied that he attempted to “stone” Mr. Ward during his deposition, but testified that it was part of the sport.

While Mr. Stewart testified that he was not attempting to stone his competitor Mr. Ward, the analysis performed by Knott Laboratory showed that Mr. Stewart’s sprint car drifted and yawed up the track in the direction of Mr. Ward at the same time engine revving can be heard in the video footage of the accident. The analysis performed by Knott Laboratory also showed that six other sprint cars in front of Mr. Stewart remained low on the race track easily avoiding Mr. Ward, while Mr. Stewart’s sprint car took an entirely different path moving up the track while yawing with his engine revving. Given the analyzed vehicle dynamics of Mr. Stewart’s sprint car, Knott Laboratory concluded that the vehicle motion was fully consistent with a “stoning” technique being attempted by Mr. Stewart prior to impacting and killing Mr. Ward.

The dispute between the Ward family and Mr. Stewart was settled just before trial.

If you are interested in learning more details regarding video analysis using matchmoving technology, please read our peer reviewed paper “Forensic Engineering Application of Matchmoving Process” by Richard M. Ziernicki, Angelos G. Leiloglou, Taylor Spiegelberg, and Kurt Twigg, published in the Journal of the National Academy of Forensic Engineers.